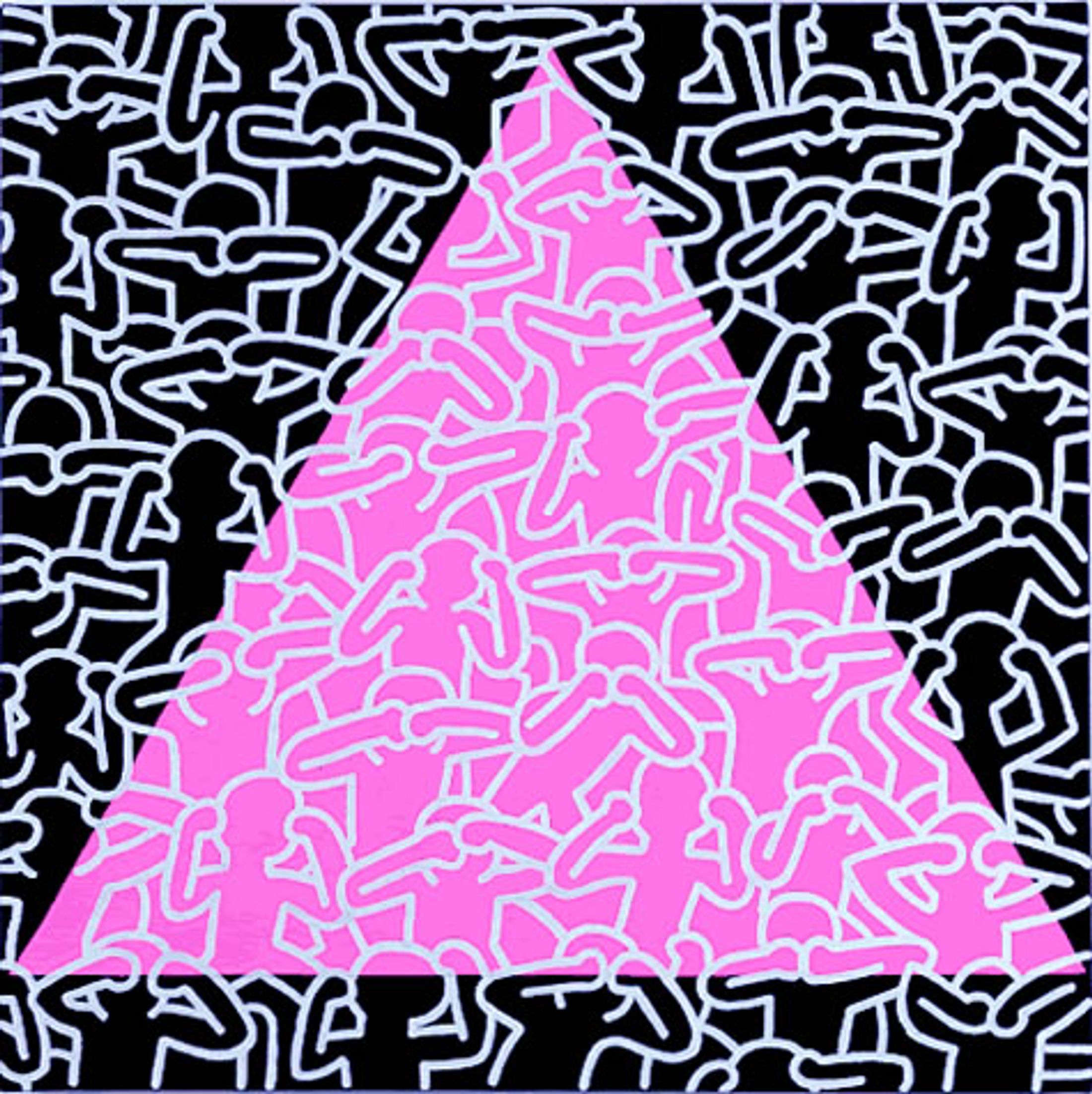

In the early 1980s, subway commuters in New York began noticing strange, chalk-drawn figures dancing across the black spaces where ads used to be. The artist was Keith Haring, a gay man who believed art belonged in the streets. His bold, cartoon-like figures spread joy, yet held a fierce political messaging.

Haring’s work tackled topics from apartheid to capitalism to the AIDS epidemic, which would eventually claim his life in 1990. His “Silence = Death” piece, created with fellow activists, became a defining image of AIDS-era resistance.

Silence = Death, 1989, Keith Haring

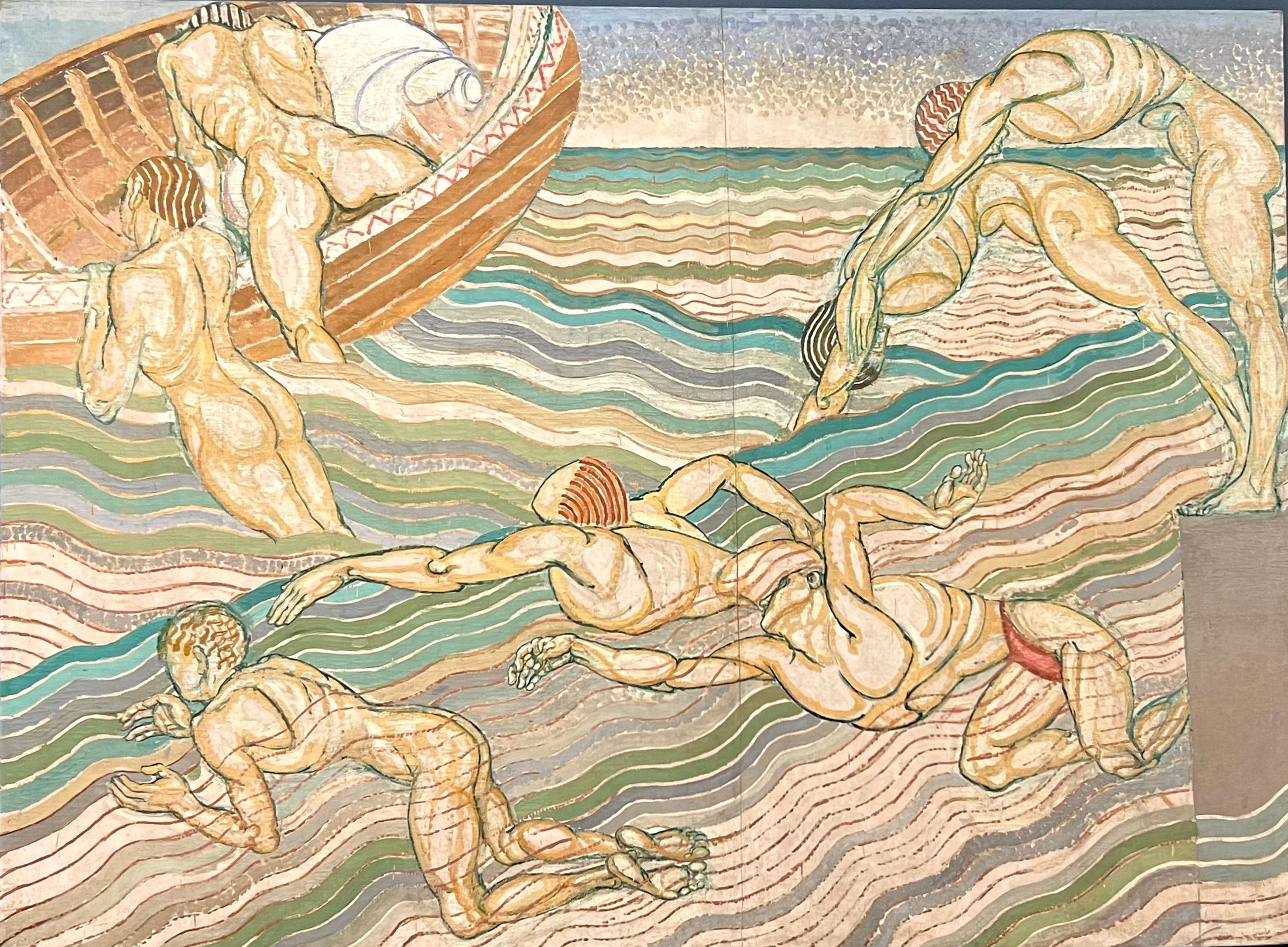

One of the most subtly radical works of early 20th-century British art, Duncan Grant’s Bathing (1911) captures a moment of male intimacy and vulnerability rarely seen in painting of its time. Depicting a group of nude men swimming and lounging together at the Charleston farmhouse, the piece radiates a quiet sensuality and camaraderie. At first glance, it appears to be a classical homage to pastoral leisure, but beneath its surface lies a coded celebration of queer desire.

In an era when homosexuality was illegal in Britain, Grant, himself openly gay within his inner circle, used classical forms and Impressionist light to mask a deeper defiance. Bathing doesn’t scream protest; it whispers freedom, offering a tender, subversive vision of male beauty and same-sex connection that challenged the norms of Edwardian society.

Bathing, 1911, Duncan Grant

Today, the political charge of queer art is no less urgent. Zanele Muholi, a South African visual activist, uses photography to rewrite the narrative around Black queer identity in a country still grappling with homophobia and transphobia related violence.

Their portrait series, Faces and Phases, captures Black lesbians, transgender, and gender-nonconforming individuals with dignity and pride. Each image is an act of resistance—against erasure, violence and invisibility. “I’m producing this work for posterity,” Muholi says, “so that future generations will know we were here.”

Anjelus Manuel Silva, Parque Augusta, São Paulo, 2024 © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

Collen Mfazwe, August House, Johannesburg, from the series Faces and Phases, 2012 © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

Queer art has always existed in tension: beauty and pain, celebration and struggle. It has often been forged in spaces of exclusion and yet, it has endured. More than that, it has transformed culture itself.

Today, queer artists are using digital media, performance, sculpture, drag, film, and textile to explore intersections of race, gender, migration, and desire. Their art is not only about identity, it’s about systems. It challenges the viewer to question who is seen, who is heard, and who decides.

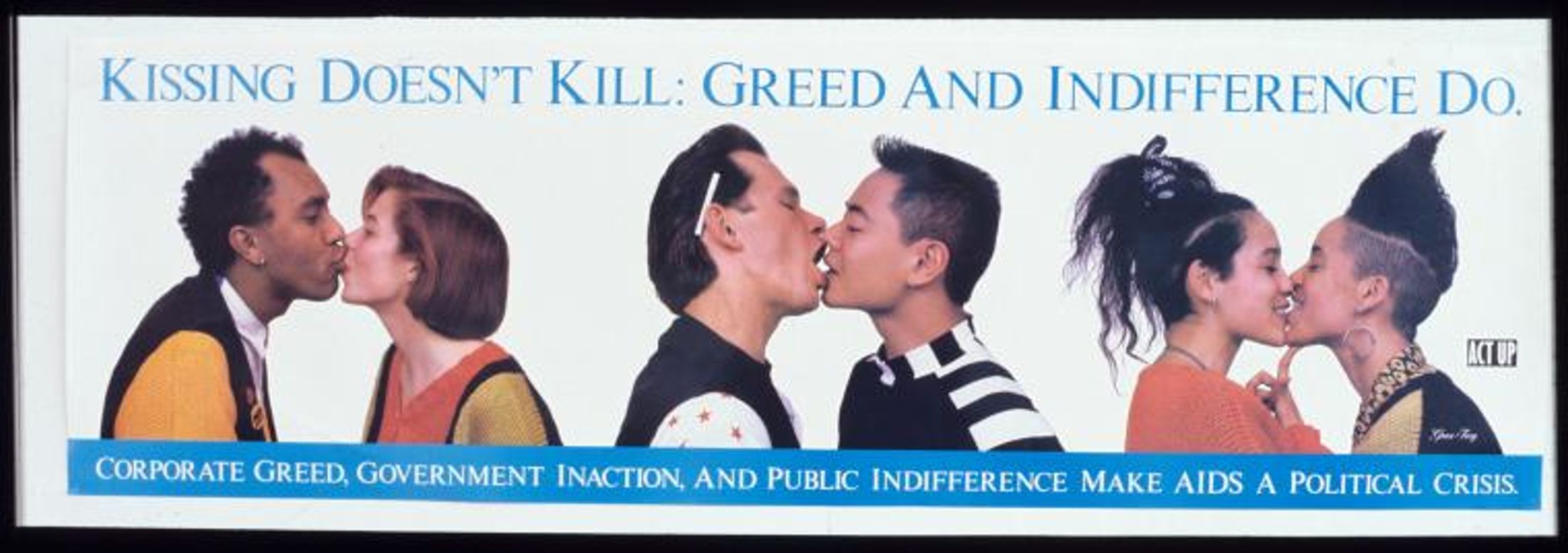

Kissing Doesn't Kill. Greed and Indifference Do. 1989, Gran Fury

As Pride becomes increasingly commercialised, the radical roots of queer art risk being glossed over. However, only understanding queer art as “representation” misses the point. Its power lies in activism.